Chapter 3

Emotions, Fears and Relationships

Unpack this topic

Sometimes you have to go through things and not round them.

"Being told you have cancer is a major event in your life. What thoughts and feelings you have are not as important as what you do with them."*

Many people feel a complicated set of emotions and reactions when they finish treatment. While they may be relieved and happy that treatment is over, they may also feel sadness, anger or anxiety about the future. How people approach their recovery and cope with their challenges will affect their emotions and the level of distress that they may experience during this time. ‘Distress’ is a term that is used to describe the unpleasant emotions that can occur during difficult times, and that can interfere with the ability to cope. While it is normal to have some level of distress as a result of being diagnosed with cancer and having to go through treatment, it is also important to be able to understand it, to find ways to work through it, and to get help if it becomes overwhelming. When people try to deny or hold in their emotional distress, they may find that the emotions get stronger and more difficult to deal with.

There is no wrong way to feel when you are emotionally distressed. The experience of diagnosis and treatment is individual to everyone and the emotions and reactions that come with this experience can vary widely from person to person. Common unpleasant emotions and reactions include:

- Sadness

- Depressed feelings

- Anxiety

- Anger

- Fear

- Loneliness

- Less sexual drive

- Crying

- Confusion

- Feeling a loss of control

- Irrational thoughts (thoughts that don’t seem to make sense)

- Difficulty sleeping

- Poor concentration

- Panic

"Unpleasant emotions are not the problem; they are the signal of a problem or your body’s response to a problem."*

It is not unhealthy to experience strong emotions, unless they get in the way of recovery and being able to move forward with life. For example, unresolved emotional distress—emotional distress that has not been worked out—may prevent someone from eating or sleeping well. Not dealing with emotional distress may interfere with honest discussions—about recovery with the healthcare team or make relationships with loved ones difficult. Distressful emotions may affect a person’s ability to cope well with everyday life.

The way people work through their emotions will be as unique to them as the emotions are. It is important during this time to simply recognize your feelings without judgement. Speaking with people you know and trust, with a support group, or one-on-one with someone who has been through a similar experience, can help. Some people find it helpful to write down their thoughts in a journal. If your emotions become too much for you to handle, professional counseling may be the most helpful way to deal with the situation. For support and services, see Chapter 3: Emotions, fears and relationships / Section 7: Healing over time and with support.

It is common to hear life after cancer treatment described as adjusting to a ‘new normal’. There is also often an expectation from others that the person in recovery will be able to ‘get back to normal’. It can be a challenge, and sometimes impossible, to figure all of this out. People often feel differently about things—sometimes about everything—after going through a cancer experience. Physically and emotionally, ‘back to normal’ may seem far away. Recovery can be a time to explore these changes and feelings, and to learn more about the person you are now. It can be very powerful to acknowledge the cancer experience and to think about how it may have brought about new feelings, ideas, perspectives and priorities about life. Some people may also find that previous relationships with partners, family members, friends and colleagues may need to be adjusted or clarified.

This chapter will explore the most common emotions and reactions experienced by people who have completed cancer treatment. It will also offer some ideas about how to take a closer look at relationships—with the self and with others. Whatever you may be feeling at this time, know that others have felt the same—and that it is possible to move through these emotions and regain a sense of balance and control to your life.

* Harpham, Wendy S. Diagnosis, cancer: your guide to the first months of healthy survivorship. New York. W.W. Norton & Co, 2003, p. 163.Section 1

Feeling sad, lonely, depressed

Sadness

Recovery is a period of transition. It is normal to have feelings of sadness that come and go during this time. For people who have been through treatment, the deepest sadness often happens right after the intense activity of medical appointments and treatment sessions end. Along with the sadness, there can be a sense of abandonment (feeling that you have been left all alone) and loneliness (see next topic ‘Loneliness and isolation’). While sadness can be set off by many things in a person’s life, the reasons for sadness at this time can usually be related to feelings of loss—for the person you were before illness, of hopes and expectations, and of the assumption of immortality that human beings often have.

Acknowledging your feelings of sadness can be a step towards recovery. Keeping sadness bottled up inside takes a lot of energy that could be put to better use in the healing process. It can be very helpful to express and share sadness with people who understand what you’re going through. This could be with close friends or family members, or perhaps with people who have been through a similar experience.

Post-treatment support groups can play an important role when dealing with sadness and difficulties with adjustments. They give the opportunity, in a safe space, to share stories and experiences with others who have had a similar experience. In a support group, people can share coping strategies and talk through the aspects of recovery that they are finding to be difficult.

Actually I’m even happier now, I value every hour even more now. But right after treatment, I felt that the sadness was like—that guy, that Michael, is gone.

Loneliness and isolation

Many people experience feelings of loneliness and isolation after treatment and as they move through recovery. One common reason that people feel lonely right after treatment is over is because the constant interaction with their healthcare team ends. The withdrawal of this connection and support can be very difficult for many patients.

Patients also often experience loneliness and isolation in recovery because they feel that others don’t ‘get it’. They feel like no one can understand what they went through—or what they are still going through. Pain, confusion and fear don’t always go away in recovery. The fear of recurrence, in particular, can make you feel alone and apart from others. Communicating these feelings can also be very difficult, partly because they are not easy to describe. Also, if you are still sorting through and figuring out these feelings yourself, it would be hard to help someone else understand them.

Changes to your body can make you feel different and separate from those around you. You may feel sort of isolated in your changed body because you’re not ready to face the outside world yet. Perhaps you avoid social activities and returning to work because of this and feel cut off and alone.

You can also feel alone even if you are surrounded by supportive family and friends. It may seem like everyone is carrying on with life and you’ve been left on your own. Perhaps people don’t call or visit you as much now that treatment is over, or they don’t really want to talk about your illness anymore. Maybe they are uncomfortable or don’t want to upset you. Or maybe you don’t talk about your cancer experience because you don’t want to trouble your family and friends, or be a burden to them.

Feeling lonely is also often connected to feelings of sadness and loss. You may need time to grieve for the way life was before cancer and the person you were then, and this can make you feel isolated from others. This is a normal part of the healing process in recovery.

When I completed my treatments in hospital, everyone wanted to celebrate. They wanted to ‘ring the bell’ and congratulate me on ‘beating cancer’. Only for me, there was nothing to celebrate. I had just been through an intense trauma, my body was now ‘different’, and while I was grateful to my care staff and everyone for being there with me, I needed more time to work through what had happened, and what was still happening. It was so hard to even try to smile—I wanted to join them in their joy, but I wasn’t ready for that. And so I felt very alone.

Although it is not easy to talk about difficult emotions, expressing your feelings is one way to help you accept what you are going through and move forward. You could choose a close friend or family member to share your thoughts with, or you might prefer a support group where you can discuss your feelings with people who have had similar experiences. You can also ask your healthcare team for a referral to a professional counsellor, such as a psychologist, if you think this would be best for you.

Depression

Patients in recovery may feel that they have to be strong and brave, especially since others around them may think that the worse is over and it is now time to get on with life. But it is not uncommon for people who have been through diagnosis and treatment to feel symptoms of depression at some stage of their cancer experience, including recovery.

There will probably be good days and bad days during the recovery process after cancer treatment; everyone feels ‘blue’ or sad at times. But if the sadness does not lift—and if it is combined with other feelings like hopelessness, worthlessness, and a loss of interest in doing things, along with physical symptoms such as difficulty sleeping, poor appetite and a loss of concentration—this may be a sign of depression. The stronger these feelings or symptoms are, and the longer they last, the more likely it is that a person is dealing with depression. It is also important to note that some medications may cause depression. Speak with your doctor to get more information, or if you are concerned that you are experiencing symptoms of depression.

Depression can make it very difficult for a person to get through their day and their ordinary activities, and to appreciate the good things in their life. However, people who are depressed can get better with time and with help. Depression is a medical problem the same as any other condition or illness, and its symptoms should be discussed with a health professional just like any other physical symptom that concerns you. Once depression is diagnosed, steps can be taken to treat it.

Depression can happen to anyone at any point in their life, even if the person has always been able to cope with difficult situations in the past. Speaking with a professional about these symptoms will help to determine what has triggered them, and the best way to treat them.

Why is it important to diagnose depression?

- It is a medical condition that can be treated.

- It may negatively affect your health.

- It may make it difficult to enjoy life.

- It may make it difficult to follow through with the decisions that need to be made about recovery—changes to nutrition or physical activity, for example.

- It may affect relationships with the people you care about and who care about you.

I had tears often after my treatments. Me, who thought I was a super woman. I had a little bit of depression. I spent about two weeks in a row crying. My oldest daughter used to phone me and say, ‘Mommy, there’s something wrong with you.’ I didn’t even realize the state I was in. So I got in touch with the psychologist at the cancer centre, who really helped me. It gave me so much courage, and now I’m taking Qi Gong and meditation with a support group. I feel at home there, in a way, because you don’t tell your story, nobody asks questions, there’s a lot of respect, but there’s a unity. We all feel like we have passed through something.

Section 2

Feeling anger

The source of anger

Anger is a common emotion for people who have been diagnosed with cancer. It is normal for it to appear at any point in the cancer experience, including recovery. Anger can reveal itself in many ways, such as frustration, crying or yelling.

There are so many reasons why someone could feel angry. For example, anger often hides or covers up other emotions, such as sadness, helplessness or fear. Sometimes, it is difficult to know what to do with the feelings of anger—in fact, sometimes you may not even realize that you are angry. You may find that you become easily irritated, frustrated, or annoyed with yourself, members of your healthcare team, or with the medical system. Sometimes even with those you love.

Feelings of anger are not bad emotions in themselves, and there is certainly a place for anger to be expressed in the cancer experience. What is important, however, is what you do with the anger. If you try to ignore it or push it down—or feel that you do not have the right to be angry—this can lead to a fear of losing control. Or, sometimes anger can look like a tug of war between rage and pushing people away, as well as support. If anger wins, it can turn against the person who is angry and may eventually lead to depression.

It can be useful to explore feelings of anger and what they are all about. And, most importantly, to figure out what you want to do about them.

Working through anger

It is important to understand the difference between expressing anger and acting on angry feelings. Expressing anger, for example, could be discussing how you feel with someone in a calm setting. Acting on angry feelings would include yelling at someone for no clear reason.

Whatever the cause of the anger, and whatever reactions result, it is helpful to express your feelings in a meaningful and safe way. It often helps to talk to someone about the reasons why you might be feeling angry. This person could be a trusted friend, family member, or a professional. Keeping a journal of your feelings and thoughts can also be helpful. Sometimes, directing your emotions into an activity you enjoy, such as exercise or a hobby, can be very useful to help let go of difficult emotions, such as anger.

When anger has been identified and expressed, the way it looks, how you see it, and how it affects you, can be changed. You need to have an understanding of anger, and a certain level of acceptance of it as an emotional reality, to successfully deal with it.

Anger can sometimes be a challenging emotion to deal with, but it is important to see it as a normal one. It is not that anger is bad—it is what you do with it that counts. It’s important to take the time to explore or understand what the feelings of anger might be telling you. Often the anger represents or masks other emotions such as fear or sadness. Don’t run away from feelings of anger, such as keeping it ‘bottled up inside you’. Simply take the time to understand what it is telling you.

Complementary therapies may also be a helpful way to work through emotions, as they focus on overall wellbeing. Complementary therapies include art therapy, healing touch, meditation and aromatherapy, to name a few. For more detailed information about complementary therapies and how they can help, see the Canadian Cancer Society booklet, ‘Complementary Therapies’, at: www.cancer.ca/en/support-and-services/resources/publications/?region=qc. Community resources for complementary therapies can be found in Chapter 2: What to expect after treatment / Section 7: Programs to help you move forward.

Top tips

The best way to deal with anger is to identify it and find a healthy way to express it. Consider the following tips when you find yourself feeling angry:*

- Recognize your anger. Sometimes people act on their anger before they know that they are struggling with this emotion.

- Avoid taking out your anger on others. Direct your anger at the cause of the feelings, rather than at other people.

- Don’t let anger hide other feelings. People sometimes use anger to hide painful feelings that are difficult or uncomfortable to express, such as sadness or hopelessness.

- Don’t wait for anger to build up. Express your feelings as soon as you recognize them. If you hold them in, you are more likely to express anger in an unhealthy way.

-

Find a safe way to express your anger. You can express and let go of your anger in a number of healthy ways, including:

- Discuss the reasons for your anger with a trusted friend, family member or professional.

- Do a physical activity.

- Yell out loud in a car or private room, even if you end up crying.

- Explore therapies, such as massage, relaxation techniques, or music or art therapy.

* Cancer.Net. ‘Coping with Anger’. Alexandria, VA, Jan 2016. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Web. Accessed June 6, 2016.www.cancer.net/coping-with-cancer/managing-emotions/coping-with-anger.

Section 3

Feeling anxious

Anxiety is the body’s natural response to danger and is connected to our survival instinct. Anxiety has kept human beings safe for many thousands of years!

Like anger, anxiety shows up in many different ways, such as worry, uneasiness, fear, uncertainty and suspicion. These feelings are the body’s way of telling us that we may be threatened in some way. They are like an alarm that goes off in times of stress, when we feel under pressure, or when situations are (or seem) risky or dangerous.

Anxiety is not necessarily a bad thing—it can encourage and motivate us to find answers to our questions and worries. It becomes a problem when we do not find solutions, and it ends up interfering with recovery and normal daily life.

During recovery, it is very common to experience anxious feelings about what will happen next. Whether these feelings are realistic or unrealistic (likely to happen or unlikely to happen) doesn’t matter—they are all true concerns for the person having them. The important thing during this time is to be aware of what is causing the anxiety and find a way to manage it. This could include talking about it with someone you trust, such as a family member, friend or professional, and finding ways to help you relax and sleep well. It is also important to go to your follow-up appointments and stay informed about what is going on with your health. And always listen to what your body is telling you.

It is also possible to feel higher levels of anxiety because of a lack of proper sleep, medications (such as steroids) or medical conditions (such as a thyroid problem). If are concerned about these possible causes of anxiety, you should talk to your healthcare team.

One of the most common worries after treatment is the worry that the cancer will come back. This worry is most common during the first year of recovery and can fade gradually over time. Section 5 of this chapter speaks honestly about the fear of recurrence, a form of anxiety that is specific to the cancer experience. Knowing what this fear is about, how it can affect the body and mind, and learning how to apply tips and strategies to put this fear in its place, can help with the recovery process after treatment.

Section 4

Body image concerns

Body image covers a group of ideas about how you think, and what you believe, about your body. This includes:

- How you see your body and how you think your body looks.

- How you feel about the way you look—or think you look.

- How you think your body works—or should work.

- How you think others see your body. This can be different from the way you see yourself.

Body image is also closely connected to self esteem, which is how you feel about yourself as a person in general. Any change in how your body looks or works can affect how you think and feel about your body, and it can also affect your self esteem and your confidence about yourself.

Cancer and changes to the body

Cancer and cancer treatment cause many changes to the body that can affect how it looks, feels and works. Depending on the type of cancer and treatment, changes can be temporary for short or long periods of time, or permanent. Many changes, such as hair loss or loss of part of the body, are visible and, perhaps, more easily thought of as causing body image concerns. But there are also many less noticeable, and even unseen, changes that can affect your thoughts and feelings about your body.

Common cancer-related changes to the body include:

- Hair loss—also hair growing back a different colour or texture

- Loss of a part of the body—such as breast, organ or limb

- Needing an ostomy

- Scars from surgery

- Skin changes—such as redness, itching or sensitivity

- Weight gain or loss

- Peripheral neuropathy—usually numbness or tingling in the hands or feet caused by nerve damage from chemotherapy

- Lymphedema—swelling of a part of the body, such as an arm or leg

- Early menopause

- Loss of fertility (not able to conceive children)

- Loss of sexual drive or difficulties having sex

- Trouble swallowing or eating

- Fatigue—feeling tired all the time

- Memory or concentration difficulties

- Problems with balance or coordination

- Speaking or breathing problems

- Changes to how the bowel or bladder works

- Muscle weakness

How these changes can affect your body image

Body image concerns are a common problem for recovering cancer patients. All cancer patients, regardless of the type or stage of cancer, or the treatment, have to deal with some degree of adjustment to their body image—even if treatment went well and even if the side effects were minimal. You may think and feel differently about your body even if the changes are not visible to others and even if there are no permanent changes.

Perhaps you feel uncomfortable in your body—or you feel disconnected from your body and don’t feel like yourself anymore. Maybe you don’t like the way you look now. Possibly the changes you’ve experienced make you feel less attractive, less feminine or masculine. Side effects like fatigue and concentration issues may make you see your body as more vulnerable or less strong. You may feel that you can’t depend on your body anymore or that your body has betrayed you. Any of these thoughts or feelings can negatively affect your body image and sense of who you are as a person.

Other changes that can affect your sense of identity or who you are as a person—which is a component of body image—include changes to your values and priorities, to your sense of what is important. For example, changes in how you view your job or relationships may represent a ‘shift’ in your sense of who you are as a person, and these feelings are a part of your identity.

Impact on your life

Any change to the body can be hard to accept and some changes can also be hard to get used to, such as an ostomy or a breast implant. It is normal to feel sad, angry, anxious, or upset—or all of these emotions—because of changes to your body that you experienced because of cancer. A device like an ostomy or a change in the breast needs time to be integrated into your sense of yourself and body. Negative feelings and thoughts about your body can also affect your sense of self—who you were before getting cancer—and your confidence and self-esteem. How you feel about the changes to your body can also affect how you interact with others, even if the changes can’t be seen.

Many recovering patients want to get back to some kind of normal life, and a normal way of thinking about life, as quickly as they can. Physical changes can be a constant reminder of what has happened to you. You might worry that you’ve lost your normal life forever—that side effects like fatigue will prevent you from doing the activities that you enjoyed before cancer or that memory and concentration issues will make it difficult for you to get back to work full-time.

Your sexual life can also be affected by physical changes and body image concerns, which is a source of great distress for many recovering patients. Some changes may interfere with your ability to have sex—but how you feel about your body can also be an obstacle in participating in any kind of intimacy or even in showing affection. This can be a challenge for people who have partners as well as for those who would like to have a relationship in the future. Patience and communication are important tools in moving forward with your sexual life after cancer. For more information on this topic, see Chapter 2: What to expect after treatment / Section 2: What are the possible side effects? / Heading: Changes in sexuality and intimacy.

Negative thoughts, feelings or emotions about your body can be confusing and hard to sort out, and can complicate your recovery. And there is a need to mourn and grieve the changes that have occurred, as there is an element of ‘loss’ associated with these changes. However, there are many strategies that you can try to improve your body image and move forward to a ‘new normal’ with confidence (see ‘Strategies to help improve body image’ below).

Dealing with the outside world

If you have visible changes to your body, another challenge may be that you have to sometimes deal with reactions and comments from others—positive and negative—including sometimes from people you don’t know. This can be especially difficult if you are still trying to come to terms with these changes yourself.

It might be a good idea to think ahead about how you would like to respond to comments or reactions about your appearance. Don’t hesitate to say that you prefer not to talk about it if someone asks you a question—even if it’s a friend who you know is just trying to be kind. This can help you feel more in control of the situation and less stressed about being out in the world again. For more tips on how to handle reactions and comments, go to: www.macmillan.org.uk/cancer-information-and-support/impacts-of-cancer/changes-to-your-appearance-and-body-image/managing-reactions-to-changes-in-appearance.

You could also think ahead about other ways to take charge of, and manage, visible changes to your body, if this is important to you. You could explore new types of clothing or bathing suits, hair styles, or even a different style altogether, if this would make you feel more comfortable and in control.

Managing work situations

How you feel about visible changes to your body may affect how comfortable you feel at work and how you interact with your colleagues. This is also something that may take time for you to adjust to. Remember, you do not have to discuss anything about your cancer experience with colleagues or your employer. If you feel uncomfortable because of comments or treatment in your workplace, don’t hesitate to bring this up with your employer or human resources. For more information on your rights at work, see Chapter 5: Back to work.

Signs you may need help coping

Adjusting to changes to your body resulting from your cancer experience can take time—this is completely normal. There are also many self-care strategies and support services you can try to help you adjust and accept your ‘new normal’ (see ‘Strategies to help improve body image’ and ‘Resources’ below). But if you feel that it is taking too long, or that you are struggling with your feelings so much that it is interfering with your quality of life, it might be a good idea to talk to a professional to help you work through and understand your feelings, and cope with these changes. Talk to your healthcare team about your concerns—if necessary, they can refer you to a psychologist.

Some of the signs that you may need help coping include:

- You’re embarrassed by the way you look.

- You don’t want to leave the house because you don’t want people to see you.

- You don’t want to meet new people or date.

- You don’t want to undress in front of your partner.

- You avoid intimacy and sex because of how you feel about your body.

- You’re avoiding returning to work because you’re nervous about what people will say or think.

- You won’t look at yourself in mirrors.

- You feel ashamed about getting cancer.

- You are not able to accept yourself as you are now.

Strategies to help improve body image

There are many self-care strategies you can try to help you accept the changes to your body and move forward.

- Give yourself time. Give yourself time as your recover from your cancer experience—time to grieve changes to your body, time to heal, time to adjust and cope. There is no schedule for this—some changes may require more time to accept and adapt to than others, and some people may need more time to come to terms with what their body has gone through. Everyone’s experience is their own. Try not to get frustrated if one day you feel good about your body, but the next day you feel less positive. This is just part of the process of adapting to changes. Be patient with yourself as you find your way.

- Identify things about your body that you like. Make a list of the things about your body that you like or are comfortable with, such as your smile, the colour of your eyes, or the shape of your hands. Try to identify and appreciate all the ways in which your body supports you in your everyday life—all the activities it helps you accomplish—without comparing anything to how things were before treatment.

- Remember that your body is only one part of you. Try to take a step back and see your body as only one part of who you are. If you only focus on the changes to your body or what your body looks like now, it is easy to forget all the other things that make you the person you are. Think about the parts of your identity that haven’t changed—such as your strengths and talents, what you’ve accomplished, what gets you excited, people, places or activities that make you happy.

- Nurture your body. Take care of your body—eat well, get enough sleep and be as active as you can. These basic elements of good health can help strengthen your body and mind, and may help make it easier to copy with changes. For information on healthy living, see Chapter 4: Regaining function. Take the time to do nice things for your body. Explore activities that help you relax or that you associate with feeling good about your body. This could be some kind of exercise, taking a long bath, or getting a massage, haircut or manicure. You could also try learning a new physical skill, such as yoga, which could help you build confidence in your body. Get together with friends who make you laugh. Looking after your body in positive ways can contribute to improving how you feel about it.

- Practice self compassion. Being kind to yourself is particularly important when you are going through a difficult time or when you don’t like something about yourself. Don’t ignore your suffering—ask yourself what you can do to take care of yourself and to feel some comfort. Be kind and understanding about what you are going through, not critical. Practicing self compassion can help lower your stress and anxiety, and help you feel less alone. For more information on this topic—including exercises and guided meditations—go to self-compassion.org.

- Find out about interventions. Don’t hesitate to consider interventions—such as reconstructive surgery, prosthetic devices or cosmetic procedures—if you think they could help improve your body image. Surgery, for example, can be used to reduce scars or rebuild tissue that was removed. Some patients even get their scars tattooed! Talk to your healthcare team about the options available to you.

- Write about it. Keeping a journal can be a very effective way to work through your thoughts and feelings. You can even just jot down in bullet form how you feel or what’s bothering you each day, if you don’t feel like writing a lot. For more information about the benefits of journaling and tips on keeping a journal, see ‘The Power of Writing’ blog at Cancer.Net: www.cancer.net/blog/2014-06/power-writing.

- Talk it out and get support. It can be very helpful to talk about the changes you’ve experienced, particularly if you have negative feelings about your body. These are common, real concerns for recovering cancer patients, and trying to ignore them, or keeping your feelings to yourself, can make moving forward difficult. You could talk to anyone you trust and feel comfortable with, such as your partner, a close friend or a psychologist. Your healthcare team can help with a referral for professional counselling, if this is what you prefer. Many people like sharing their feelings with others who have had similar struggles, and finding out how they coped. This could be one-on-one or in a support group, in person or online—there are many options.

Resources

Below are some of the resources available for information and support for body image concerns. Ask your cancer centre about resources available where you live.

- ELLICSR Health, Wellness, and Cancer Survivorship Centre: www.ellicsr.ca/en/connectwithELLICSR/ellicsr_newsletter/Pages/2018/rebic.aspx. Offers a free 10-week support group program on restoring body image after breast cancer, led by professionals.

- Look Good Feel Better: lgfb.ca. Program to help women feel good about themselves after cancer treatment. Includes resources for different topics, and in-person and online workshops.

- Canadian Cancer Society–Coping with body image and self-esteem worries: www.cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/living-with-cancer/your-emotions-and-cancer/coping-with-body-image-and-self-esteem/?region=qc.

- Cancer Chat Canada: cancerchat.desouzainstitute.com. Includes resources and online support groups led by professionals.

- Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre: sunnybrook.ca/content/?page=pynk-education-body-image-breast-cancer. A resource for breast cancer patients with body image concerns.

- Healthtalk.org: healthtalk.org/living-and-beyond-cancer/body-image. Includes videos of people with different types of cancer talking about body image.

- LIVESTRONG: www.livestrong.org/we-can-help/emotional-and-physical-effects-of-treatment/body-image. Includes videos from cancer patients struggling with body image.

- Cancer.Net: www.cancer.net/coping-with-cancer/finding-social-support-and-information/online-communities-support. Includes numerous links for online support groups and one-on-one support.

Section 5

The fear of recurrence

Just imagine with me that your frightening thoughts are like voices on a radio. They can be controlled by changing the volume. When the volume is up too high, the noise (your fear) is so loud you can’t hear or think of anything else. But you can turn the volume down, so low that you still hear the noise (your fear) in the background, but it doesn’t bother you so much, and you can concentrate on other things.

What is this fear about?

After a cancer experience, it is perfectly normal to fear that the cancer will return. This fear is most common during the first year post-treatment, and for most people it gradually fades over time. The fear of a recurrence may not be present all the time—some people feel most anxious before medical appointments, for example, or when they reach a milestone, such as the anniversary of their diagnosis. Anxiety may also appear unexpectedly at important moments in a person’s life, or in the lives of the people close to them, such as at weddings or on birthdays.

The fear of recurrence can have its roots in many different worries. It is often connected to general uncertainty about the future and concern about how well the treatment worked. Many people worry that they would not be able to face another cancer diagnosis, and dread the idea of re-living the experience of treatment, and the way it affected their body, their life, and their emotions.

How does this fear affect you?

Fear of recurrence can prevent you from looking forward to returning to daily life. It can block you from focusing on your recovery, from enjoying the present moment, and from making plans for the future. Some people wish they could return to the pre-cancer period of their life when they didn’t have to worry about a life-threatening situation. Others are motivated to make lifestyle changes because they fear if they do not make these changes they will have a recurrence. This behaviour can lead to a great deal of stress and anxiety, as the focus remains on the illness and not on a choice to live the healthiest and best life possible.

Identify the source of this fear

It’s important to face the fear of recurrence in order to be able to move forward with your life. A good first step is to try to understand where it is coming from and what seems to set it off. Once you understand what triggers this fear, you will be able to take steps to manage it.

The fear of recurrence may be connected to thoughts or worries that now seem to be a big part of your life. Perhaps the worries lead to behaviours that increase your anxiety, such as constantly checking your body for signs of cancer. Some common sources for the fear of recurrence are described below. Further in this section, you will find tips and strategies on what to do to help manage this fear.

Anxiety about your health

Some people deal with anxious or fearful thoughts by trying their hardest to avoid them, or by pretending they do not exist. As you may already know, the more you try to stop thinking about something, the more you tend to think about it. This can lead to an increase in anxiety.

Avoiding actions or activities that may lead you to think about your fears will not be helpful in the long run. For example, someone may avoid asking their doctor certain questions, or even not show up for a medical appointment, so that they will not have to deal with the possibility of bad news. But sometimes not knowing can make things worse, and can end up increasing anxiety.

Another way some people deal with anxiety about their health is by constantly looking for reassurance that nothing is wrong. They may do this by seeing many different doctors for multiple opinions, searching over and over again for information online, or by checking their bodies all the time for signs of recurrence. While it is healthy to be informed about your health, it’s important to recognize if you’re going about this in a negative way.

I guess after treatment my expectations were that since I was done, I’d be back to normal right away, back to my old self. I guess I was in denial, because everyone else saw it, and the nurses told me that it was time for me to realize what I went through. I was like, no, I’m fine. I don’t know what you’re talking about. I mean, I was strong throughout the whole six months, why do I need you guys now? I was always very positive throughout my treatment. I guess they saw me as a ticking time bomb, and they were right. When I went back to work, I lasted maybe two weeks. Then I had to admit to myself that it was time for me to just relax. I stayed at home for nine months, and when I went back to work the re-entry was much better.

Feeling a loss of control

When a person is in cancer treatment, they are in a setting that is, for the most part, structured by their treatment plan and controlled by the healthcare professionals caring for them. By following the treatment plan, the patient participates in this control. At the end of treatment, when all of these very detailed activities are over, people often feel a sudden loss of control or structure in their lives, and this can be very unsettling and distressful. When speaking about their recovery, people often talk about feeling abandoned and alone during this time. This is a very normal reaction during the recovery period. It can be a challenge, and it can take some time to learn how to manage life again—which may not be the same as before treatment—and to regain a sense of order.

Imagine a person in an unfamiliar city who takes a bus. The bus driver (healthcare professional) knows exactly where the person needs to stop (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy), and at each stop there is an expert that takes over to give directions. The bus line ends at the stop called ‘end of treatment’. When the ride is over, what happens when the person is left to explore on their own? It would not be unusual to ask: ‘How should I take it from here by myself?’

Nothing was expected of me during treatment, and I got all this amazing care, attention and TLC—and then it was gone. I thought that I should be happy, I’m finished treatment, I can go plan my normal life again. And still I was thinking, yeah, but I kind of miss the hospital, which you kind of feel stupid for thinking. So I think it would be important to counsel patients when they finish their treatment that this is a totally normal state of mind.

Feelings of uncertainty

No one plans to become ill with a serious disease—a cancer diagnosis is mostly an unpredictable event. After treatment, many people feel anxious about what may happen to them in the future. This is normal, as, in general, human beings like a certain amount of order and predictability. But it is also true that everyone faces uncertainty every day of their life. We cannot completely control what will happen to us.

Some people have a habit of worrying a lot about the future or the unknown, which is a way of trying to prepare for anything that might happen. In reality, though, excessive worrying or the inability to deal with uncertainty can cause anxiety. Some people also try to remove uncertainty from their life by avoiding situations that cause anxiety, or by constantly seeking reassurance from others that everything is alright. Although they may feel that they are controlling uncertainty by doing this, they are also continuing to worry. And any comfort that they get from doing these things won’t last long.

You can learn how to be accepting of uncertainty by taking steps to manage how much the fear of the unknown affects you, and by making decisions that will have a positive influence on your life.

Existential worries—the big questions

Having cancer and coming face to face with death and dying can lead people to ask themselves questions that cannot be answered easily: Why me? What is my purpose in life? What do I believe? Who am I now? While the threat of death can inspire some people to change their life or focus on what is really important to them, it can lead others to feel very lost. Some people have described it as a kind of disconnection—with their bodies, their sense of self, their spirituality, and with the people around them. What a person has always known, and perhaps taken for granted, no longer comforts them. Recovery is a time when you can think about what you have gone through, where you feel you are now, and what is important to you going forward.

Time is an important part of the healing process after cancer treatment. It takes time to reconnect with priorities and purpose, to find the best way to deal with what has happened, and to look forward to the future. It can also be comforting to look for a sense of meaning in the cancer experience. This might involve exploring the purpose of life or setting new priorities and goals. Focusing on what is truly important to you can help you shift your attention and move worries into the background.

Fear of recurrence measurement

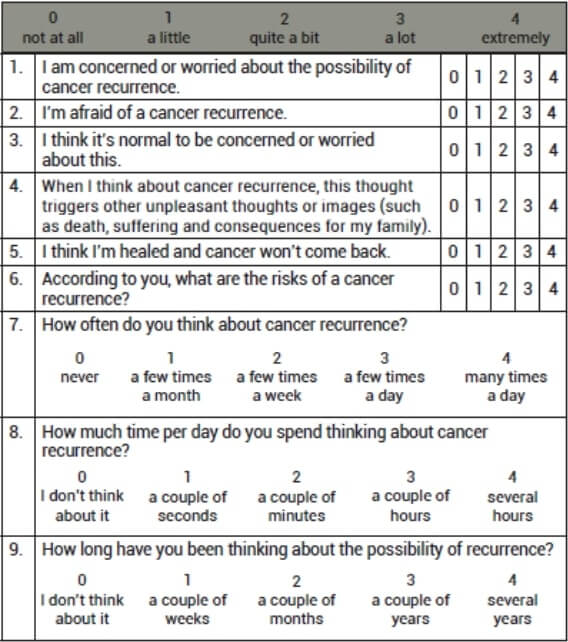

The fear of recurrence is a type of anxiety that is specific to the cancer experience, and everyone faces it in their own way. In general, most people feel this anxiety most often during the first year of recovery, particularly during the time leading up to medical appointments. For others, the fear of recurrence may stay with them for a longer period of time. It is important to remember that the strength of this fear has no relation to the actual risk of recurrence. The following questions can help you measure how you feel about the fear of recurrence.

Is your fear too much?*

Add up the numbers you circled for each question. If the total is 13 or more, you may want to speak to a health professional about your concerns.

* Translated from French and exactly reproduced from: Savard, Josée. Faire face au cancer : avec la pensée réaliste. Montréal: Flammarion Québec, 2010, p.99.

Dealing with the fear of recurrence

Identify your triggers

Take the time to think about what sets off your fear of recurrence. For some people it shows up before a medical appointment or test, or before an important personal event, such as a birthday, anniversary or family member’s wedding. Think about the things that you have done in the past that have helped you reduce your anxiety, and try doing the same thing before situations that you know bring on your fear of recurrence. For example, if exercise, watching a movie or taking a walk by the water usually helps calm you when you are stressed, these things may also help you manage this fear.

Put fear in its place

It is important to recognize that it is normal to have some concerns about your health. It can even be helpful at times, as it can motivate you to make positive choices about your health and overall wellbeing. For example, some people decide to join a walking club, include more fruits and vegetables in their diet, renew a relationship with a family member, or speak to their employer about adjusting their work responsibilities. It can also be helpful to have a good understanding of what is involved for your follow-up care and to discuss your concerns with your healthcare team. They can often help you to see where the fears are coming from, discuss with you how real they are (or are not), and inform you about behaviours and lifestyle changes that may help you reduce the risk of recurrence—which may also help manage your fear.

To be able to move forward, you have to look forward and focus on the things you can actually manage. This will help you regain a sense of control over your life and keep fear in its proper place. To help you focus on what you can manage and control, make plans and take realistic steps, such as in the following list.

This week, I am going to:

- See friends.

- Try a new recipe.

- Meet a work colleague for lunch.

- Meet with my healthcare team for my follow-up plan.

- Practice relaxation exercises.

Take care of your health

Worrying about something that you have no control over can affect your emotions and your daily life. However, by taking the best possible care of your body, and focussing on being healthy, you can help reduce your fears and develop a sense of wellbeing.

A healthy diet and being active can improve the overall wellbeing of anyone—for people in recovery from cancer treatment, these activities can also help give them an important sense of control over their bodies. Regaining function and health can help you recognize the difference between normal aches and pains and possible cancer-related symptoms. And this may also help reduce your fears. For more information about living a healthy lifestyle, see Chapter 4: Regaining function. For more information about side effects and their symptoms, see Chapter 2: What to expect after treatment.

Relaxation exercises

Reducing stress is an important part of taking care of your health. One way to help manage stress and worrying is with relaxation exercises. These can take some practice when you are not used to doing them regularly, but you should notice the benefits pretty quickly. Try to practice in a place that is quiet and where you feel comfortable. The following is an example of a ‘body scan’ relaxation exercise:

1. Chose a comfortable place where you can rest for at least 20 minutes. Put a note on the door or tell people that you need this time and space to relax so that they won’t disturb you. The room should be a place where you feel that you can easily relax. Make sure that the lights are not too bright and that the chair, couch or mattress will be comfortable for you for 20 minutes.

2. Sit or lie down, whichever you prefer. Loosen any tight clothes and close your eyes.

3. Begin by focussing on your breath. Be aware of breathing in (inhaling) and breathing out (exhaling). Let your thoughts just come and go and keep breathing.

4. Continue to be aware of your breathing and release the tension from your muscles one at a time. Start with your face (forehead, eyes, lips, jaw and neck), and then keep moving down your body: shoulders, chest, stomach, lower back, buttocks, thighs, calves and feet.

5. Focus on each muscle until that part of your body feels heavy and warm. Repeat to yourself, ‘my leg feels heavy and warm’ until your leg feels that way. Continue with the rest of your body until you feel that it is relaxed.

Relaxation tools:

- Breathe to relax–National Center for Telehealth and Technology (free app): appadvice.com/app/breathe2relax/425720246

- Relaxation melodies (free apps): play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=ipnossoft.rma.free&hl=en&gl=US

- Relaxation videos: youtu.be/HmTLdhDFXs0

- Guided imagery video: youtu.be/cphfl9DQKyY

Stay informed

Being informed about your health can help you look at yourself and your future more realistically. Knowing what you can do for your health, and being involved in your follow-up care, can help you develop a sense of control.

There is increasing evidence suggesting that a positive lifestyle is helpful for overall survival. This includes healthy eating, being active, limiting alcohol intake, and stopping unhealthy behaviours, such as smoking or excessive sun exposure without sunscreen. Your healthcare team can help you monitor other risks, such as genetics (inherited risks), family history, age at time of treatment, type of primary cancer and type of treatment. Talk about possible risks with your healthcare team and develop a care plan with them that is right for you.

The fear of recurrence is a perfectly normal response for a person who is in recovery. Discussing your follow-up care plan with your oncologist, knowing when and why you will be seeing them, and understanding what testing will be done can help lessen your fears. Being informed will help you understand that not every ache and pain is a sign of recurrence. If you are worried or concerned about a persistent pain or symptom, make an appointment to see your oncologist who will reassure you or investigate further if necessary. That’s why we are here.

Learn to live with uncertainty

Trying to control uncertainty is not only impossible—it can also affect your physical health and emothional wellbeing. There are strategies that can help increase your ability to tolerate (to live with) uncertainty.

Strategy 1: Challenge your need for certainty.

- Ask yourself if it is really necessary to be certain (to be sure) about everything. When is it really important?

- Make a list of things you like to be certain about and those where uncertainty is ok.

- Ask yourself if you usually predict bad things will happen when you are uncertain about something. Next, ask yourself if it is possible that a good thing will happen instead.

- Ask people you know and trust how they cope with uncertainty. Everyone deals with this issue differently and you might be able to get some helpful tips from others.

Strategy 2: When you worry about something that may or may not happen in the future, you are not likely living in the present and experiencing your life as fully as possible. Living in the present can also help reduce feelings of uncertainty. Learning to live in the present can help to accept the past and realize that you cannot control the future.

- Be aware of your feelings of uncertainty. When you notice that you are having one of these feelings—for example, you read an article in the newspaper about cancer and it makes you think, ‘What if my treatment didn’t work?’—try to sit quietly with that feeling for a while and not do anything with or about it. Just accept that it is there.

- Make a decision to let go of any desire to immediately get rid of, or do something about, the feeling of uncertainty. Sometimes it helps to actually say to yourself, ‘I am letting go of this feeling of uncertainty’.

- Focus on the immediate present. To help you do this, look around you and notice what you see, listen to the sounds around you, notice your breathing, feel your feet on the floor, the back of the chair supporting you, etc.

- Gently bring yourself back to the present when you find your mind wandering to thoughts of uncertainty.

- Try the above tips along with the relaxation exercises described in ‘Taking care of your health’ earlier in this section.

You can try either strategy, or a combination of the two, to see what works best for you. These strategies are like exercises—the more you practice them, the better you get.

The possibility of getting cancer again is something that always stays a little in the back of our minds. It’s normal. I wouldn’t say that I’ve become a hypochondriac, but when I get a pain I think: Woops! What did I do yesterday? Oh, yes, I pushed a wheelbarrow that was full of dirt. Okay, that’s why I’m aching. We are more attentive to our bodies now, but my last scan was A1 and that reassured me. And our philosophy has changed a bit. Of course we still make plans, but life does not stop for us. The earth continues to turn, so we must live our lives in the present moment. Today is today, and tomorrow we shall see.

One thing that is difficult for most people to do is to tolerate uncertainty. As humans, we have a kind of automatic need to control things. We want our life to be as predictable as it can be. Unfortunately, life doesn’t always work that way. Many things in life are unpredictable and can cause anxiety. It is impossible, no matter how hard one tries, to erase uncertainty from one’s life. Tolerating uncertainty is, in fact, one way to cope with anxiety and fears.

Express yourself—know when you need more help

Speaking to someone you trust about your fears may help clarify them for you. If you don’t think that you would feel comfortable talking about your fears with family or friends, speak to a member of your healthcare team. You may want to consider asking for a referral to a therapist, such as a psychologist, who has experience talking to cancer patients. Support groups, where you can share your thoughts with people who have been through similar experiences, can also be helpful. For more information about support groups, see Chapter 3: Emotions, fears and relationships / Section 7: Healing over time and support.

If you do not feel comfortable talking about your feelings with anyone, another way you can try expressing yourself is by writing down your thoughts in a journal. Going back and reading what you have written may help you understand your fears better.

I have a friend who finished treatment one year before me. And I would talk to her and see her, I would see her well and with her hair back, see her back to work and with her kids—and that really inspired and helped me. So having peer support, and talking to people about those things that make you think you’re so crazy, like am I imagining this? Am I crazy? No—everyone thinks this way, it’s okay. You’re not crazy.

Some people find that creative or spiritual activities help calm their fears. Creativity can be a way to express emotions that are difficult to talk about. Ideas for creative and spiritual activities to explore include:

- Music—singing, playing an instrument.

- Writing—poetry, children’s stories, journals.

- Cooking—classes, recipe exchanges, giving a dinner party with a theme.

- Art—drawing, painting, pottery, flower arranging.

- Spirituality—consulting a spiritual advisor, yoga, meditation, Tai-Chi.

Complementary therapies may also be a helpful way to work through your emotions, as they focus on the wellbeing of the mind, body, and spirit. There are many different types of complementary therapies that you may want to explore, including meditation, reflexology, aromatherapy, art therapy, reiki, healing touch and massage therapy. For more detailed information about complementary therapies and how they can help, see the Canadian Cancer Society booklet, ‘Complementary Therapies’, at: www.cancer.ca/en/support-and-services/resources/publications/?region=qc. Community resources for complementary therapies can be found in Chapter 2: What to expect after treatment / Section 7: Programs to help you move forward.

Top tips

- Take steps to deal with your fear. Notice when your fears appear and try to let them just be for a while, instead of using energy to try and get rid of them.

- Make life choices based on positive actions that will help you. For example, you might think about an activity that you enjoy and decide to start doing it on a regular basis.

- Challenge your fears by thinking about them from a distance. For example, think about how you would react if a friend told you that they had this fear.

- Practice acceptance and living in the present.

- Be aware that your anxiety may increase in certain situations. For example, before medical appointments or tests or before the anniversary of your diagnosis, etc.

- Focus on what you can control. Work towards a healthy and balanced lifestyle.

- Don’t worry alone. Speak with someone you trust about your fears. Get support from your family, friends, healthcare team or support groups.

- Be involved in your follow-up care. Keep track of your health care and stay informed. Knowledge is power.

- Give yourself a break. Not everything has to be done at once.

- Share information that you have found on your own with your healthcare team and ask them for their opinion.

After you’ve tried these tips, fill out the ‘Fear of recurrence measurement’ questionnaire in this section. If you’ve already done this, do it again. If the result is (still) 13 or more, consider talking to a professional.

Section 6

Thinking about relationships

With yourself

Many people who have gone through cancer treatment agree that this experience has brought change to their life, which often includes setting new priorities for the future. This is one of the reasons why the time after treatment is often called the ‘new normal’. But many people post-treatment also feel that they should be getting back to their old self. Sometimes they feel this expectation from the people in their life as well. Partners, family, friends and co-workers may want you to get back to the way things were—what was considered normal—before you were diagnosed. They may expect you to be the way you were and to play the same role you used to play in their lives. Perhaps you do not feel ready to do this, or perhaps you feel that this is just not possible.

Recovery can be a time to think about your relationship with yourself, and who you are. You may want to think about how you feel about yourself now, and how these feelings are different from before your cancer diagnosis. You may want to ask yourself how your experience has changed you, and what you can reasonably expect from yourself now. As you find the answers to these questions, you may be able to gradually fit this way of feeling and thinking into how you live your life now.

During this time, it is important to try to avoid making comparisons—with the way you were before or with other people who have gone through treatment. When people make comparisons, they usually put themselves in a better or worse position than the other person, and this is not helpful. Everyone’s experience is unique to them. Also, try to avoid comparing the way you are feeling to the way you think you should be feeling, either physically or emotionally. Rather than pressure yourself to be a certain way, or to be your old self, you may want to think about recovery as a time when you are gradually moving toward a new self.

Here are some ways to get to know who you are now and create your ‘new normal’:

- Acknowledge your feelings and emotions. All emotions, good and bad, are yours and it is okay to feel them.

- Acknowledge the changes that have happened to you, and give yourself time to adjust to these changes.

- Accept that you cannot control everything. Focus and work on the things that you can control.

- Reduce stress. Be kind to yourself. Try to include relaxation and stress-relieving activities in your schedule. For more information, see Chapter 4: Regaining function.

- Set aside some time for yourself. Think about what brings you pleasure and happiness, and try to enjoy these things on a regular basis.

- Try something new. What have you always wanted to do but have never made time for? Perhaps now would be a good time to explore that.

Developing the ability to incorporate the changes you are going through is a step towards recovery. Once you are able to identify and integrate these changes, modes of expression and alternative choices will present themselves and promote a sense of personal growth. It is possible to embrace the changes and claim your humanity through an act of self-acceptance.

Just what is normal? Normal for me is a point of reference. It depends. What is normal for you is not normal for me whatsoever.

With your partner

You may feel that your relationship with your partner is stronger than ever now. Or you may feel that the challenges of treatment have led to communication difficulties between the two of you. Your relationship with your partner may also change as you go through recovery. These changes may be in addition to any relationship changes that you experienced during the treatment stage. For example, perhaps your view of life, or your attitude about life, is different now, and you are unsure how to express this to your partner. Perhaps your partner would like to get back to your regular daily routine as a couple, but you do not feel ready to do this.

It can be helpful to be aware of keeping the lines of communication open during this time, as you both work through the emotions you may be feeling. Try to figure out what kind of support you need from each other and talk about these needs. It is normal that a couple may not always be able to fulfill all of each other’s emotional needs. When this is the case, friends, other family members, counsellors or spiritual advisors may be able to help. Some couples may also need to take the time to focus on their intimate life and find a sense of connection again. For more information, see Chapter 2: What to expect after treatment / Section 2: What are the possible side effects? / Heading: Changes in sexuality and intimacy.

It is important to remember that the cancer experience affected both you and your partner. It can take some time to reconnect as you both gradually move forward into the ‘new normal’. If you feel that your partner could use some support during this time, they may find Chapter 6, ‘Family Caregiver Support’, helpful. In addition to individual therapy, support for couples is also available from the therapist on your cancer care team. For more information about support groups and psychosocial support, also see Chapter 3: Emotions, fears and relationships / Section 7: Healing over time and with support.

Subjects you may want to discuss with your partner:

- How your roles and responsibilities may change during recovery.

- What kind of support you need to help you in the recovery phase of the cancer experience.

- What your partner needs to do to help you through recovery.

- How to keep up the quality of your relationship, and perhaps rekindle intimacy.

With your family

Family members go through a period of recovery as well, and they often need time to sort out the experience that they have lived through with you. Some may continue to worry about your health and not want you to return to your daily responsibilities, even though you feel ready. Others may want to return to the way things were before treatment. Sometimes family members don’t know what to do, or may not want to express their feelings out of a concern for your emotional wellbeing.

Deciding what everyone’s role in the family will be may require a series of discussions and compromises. Good communication—of emotions, feelings and expectations—is important during this time. Some families may benefit from the help of a family therapist, especially if relationships were difficult before treatment. Parents often feel that they need to protect their children, but speaking openly with your children in a way that is suitable for their age can help them recover from the cancer experience as well. For more information about speaking to your children, see Chapter 6: Family caregiver support / Section 1: Are you a caregiver? / Heading: Talking to your children about cancer.

With your friends

People who have gone through treatment often speak about the friends who were there for them during this difficult period, as well as those friends who they felt let them down. People react in different ways to illness—some can be extremely supportive, while others feel uncomfortable with it or want to avoid it completely. During recovery, friends may also be unsure of what to do for you, or expect that this is the time when you return to normal life and the friendship that you had before your diagnosis. It can be challenging if you feel that you are a different person now, or if you are dealing with emotional or physical side effects that you need to talk about with those close to you. If you feel your friends do not understand your challenges during recovery, talking to other people who are going through the same experience may be very helpful. For information about support groups and services, see Chapter 3: Emotions, fears and relationships / Section 7: Healing over time and with support.

It is certainly difficult to lose friendships, but an illness experience can also bring to light which relationships you want to take care of and which ones would be better to let go. It may be better to spend time with the people who bring you positive emotional energy, rather than with those who take energy away from you. Perhaps you now have a deeper appreciation for friends you have known for a very long time. Or, new friendships you have made during your cancer experience may help support you during your recovery. Now may be the time to take care of these relationships.

That’s when you find out who your real friends are. When you’re sick. Because when you’re well, they take advantage of you. When you’re sick, you don’t see them. All the negative people, I can’t deal with that anymore.

Dating and socializing

The way you look at romantic relationships may also have changed as a result of undergoing cancer treatment and managing all the changes that it brought to your life. Physical changes to the body and side effects can add extra challenges to meeting people socially, and you may be wondering how and when to approach these subjects with new people in your life. For some people, the fear of rejection prevents them from participating in a social life, even if they are being encouraged to do so by family and friends. You might find Section 4 of this chapter (‘Body image concerns’) helpful if this is a worry for you.

Try taking small steps to help you get back into socializing. Focus on your interests first. For example, join a club or take a course in something that you enjoy. You will meet new people who share the same interests as you at the same time.

Try not to use cancer as an excuse to avoid social activities. When you meet someone and begin dating, wait until you feel comfortable enough with this person to bring up the subject. You also want to feel that you are prepared for different kinds of reactions.

Myth-busting: Cancer is not contagious and there is no risk of giving it to someone else. Having sexual relations does not increase the risk of recurrence!

Top Tips

Taking care of relationships with family and friends:

- Bring up the subject of your cancer experience directly, or suggest talking about other topics. If friends or family members are not sure what to say to you, let them know it is okay to ask about your experience. Or perhaps you can say that you would prefer to talk about the things going on in their life.

- Say yes to offers of help. Good friends and family members like to feel useful. Accept offers of help, or suggest to them how they can help you.

- Decide how you want to explain your experience and what you feel comfortable talking about. This will put both you and your friends at ease during conversations.

- Let family and friends know if you would like to be invited to social activities or family events. They may hesitate to invite you if they know you have not been feeling well.

Section 7

Healing over time and with support

It is important to know that, for most people, the emotional difficulties of the cancer experience usually decrease over time. Be patient, and kind to yourself. Give yourself all the time you need to heal. Try to remember to:

- Focus on the things you can control.

- Reduce anxiety. By spending time with friends, family, and by doing your favorite activities at the pace that is right for you.

- Get support. You never have to go it alone—support can make a difference in how well you recover and it can give you the time you may need to work through any difficulties.

For more information on managing emotions, go to www.cancer.net/coping-with-cancer/managing-emotions.

Support groups

Joining a support group or receiving support from a peer (an individual with similar experience) may help you understand and deal with your fears and challenges better. Being around other people who have lived through a similar experience to yours can be comforting. It may also be helpful for you to speak about your feelings with others who may be able to offer practical tips and advice about overcoming the fear of recurrence and recovering well. Sharing your experience may also help other people.

How to find the right support group

There are different types of support groups in the community. Because everyone is different, don’t hesitate to try them out until you find one that suits you the best. Perhaps you would prefer speaking to someone one-on-one (peer support). Peer support is also available through community organizations. Below is a sample of the support groups and peer support available in general and in some of the provinces. Use it as a guide to find more information or information in your particular area.

- Canadian Cancer Society: www.cancer.ca/en/support-and-services/support-services/how-we-can-help/?region=on. Offers monthly support groups, hosted by a healthcare professional and a trained volunteer. Provides information about the types of support groups available in your area.

- Canadian Cancer Society online community: www.CancerConnection.ca. Community members can participate in discussions and blogs, join groups and exchange messages.

- Cancer Chat Canada: www.cancerchatcanada.ca. Provides free online support groups led by professionals for those affected by cancer, including patients, survivors and family members.

Quebec/Montreal

- Cedars CanSupport (MUHC): www.cansupport.ca. This post-treatment support group is for people who have completed active treatment (chemotherapy, radiation, and/or surgery). Common themes include adjusting to life changes, addressing concerns about identity and self-esteem, and managing overwhelming emotions and fear of recurrence.

- Groupe de soutien du cancer de la prostate: soutienprostatechum.org/actualites. A monthly support group for men living with prostate cancer, usually with a presenter who is a survivor of prostate cancer leading the meetings. French only.

- Hope & Cope: www.hopeandcope.ca/peer-support/#support. Offers a post-treatment support group and can organize one-to-one peer support.

- Quebec Cancer Foundation Info-Cancer line: fqc.qc.ca/en/need-help/psychological-support/telephone-peer-matching . Provides support and information. Staff can help organize peer-to-peer support, answer questions and refer you to resources in your area.

- West Island Cancer Wellness Centre: www.wicwc.org. Offers support groups, private counseling and a variety of complementary therapies.

Ontario/Toronto

- Wellspring: wellspring.ca/online-programs. A community-based cancer support network, with locations across Canada. Offers support groups specific to different types of cancer. (Also available in Calgary, Edmonton, Nova Scotia, and PEI.)

- Cancer Chat Canada - de Souza Institute: cancerchat.desouzainstitute.com/calendar. Organizes support group sessions on specific topics, including treatment, post-treatment, and body image issues.

- Heart Place Cancer Support Centre: hearthplace.org/adult-programs/support-groups. Organizes a variety of support groups by type of cancer, sex, and where you are in your cancer experience.

- Gilda’s Club: gildasclubtoronto.org/course-category/support-group. Offers 8-week support group sessions for both adults and children, led by mental health professionals.

- Prostate Cancer Support: pcstoronto.ca/peer-support-2. Organizes support groups for men who have been treated for prostate cancer.

Alberta/Calgary

- Wellspring: wellspringcalgary.ca/what-we-offer/external-cancer-support-groups. A community-based cancer support network, with locations across Canada. Offers support groups specific to different types of cancer. (Also available in Toronto, Edmonton, Nova Scotia, and PEI.)

- ProstAid Calgary: www.pccncalgary.org. A support group for men diagnosed with prostate cancer.

- Alberta Health Services—Tom Baker Cancer Centre: www.albertahealthservices.ca/findhealth/Service.aspx?id=1047804&serviceAtFacilityID=1074213#contentStart. This cancer centre organizes support groups for cancer patients. The groups are led by mental health professionals.

- InformAlberta: informalberta.ca/public/service/serviceProfileStyled.do?serviceQueryId=1067114. A support group located at the University of Alberta Hospital for people who have received treatment for head, neck, or oesophageal cancer.

British Columbia/Vancouver

- BC Cancer—Support Programs: www.bccancer.bc.ca/our-services/services/support-programs. Lists all emotional support services available, including support groups.

- BC Cancer—Support Circle: www.bccancer.bc.ca/about/events/support-circle. For patients, friends and caregivers.

- Prostate Cancer BC: www.prostatecancerbcsupportgroups.ca. Offers support groups all over the province for men who have been treated for prostate cancer.

- Georgian Bay Cancer Support Centre: gbcancersupportcentre.ca/home/find-support/british-columbia. Provides an extensive list of support group programmes or general support classes across the province.

Consulting a professional

If you find that the fear of recurrence is severely interfering with your recovery, speak to your healthcare team—most hospital cancer centres provide psychosocial services. You can speak to a psychologist or take advantage of a program, such as the ones listed below for some of the provinces. Use this as a guide for find more information or services in your particular area.

Quebec/Montreal:

- The Cancer Rehabilitaton and Cachexia Clinic (MUHC): muhc.ca/cancer/page/cancer-rehabilitation-and-cachexia-clinic. Offers rehabilitation, nutritional counseling, and psychosocial services. Patients must be referred to this program by their oncologist.

Ontario/Toronto

-

UNH Princess Margaret Cancer Centre—Psychosocial Oncology Clinic: www.uhn.ca/PrincessMargaret/Clinics/Psychosocial_Oncology. Provides family and individual counselling with therapists, psychiatrists, and social workers for patients of the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre. A referral is required.

- A general psychology service is also offered. A referral is required, but you do not have to be a patient of the Cancer Centre to receive these services: www.uhn.ca/PrincessMargaret/PatientsFamilies/SpecializedProgramServices/Pages/psychology.aspx.

Alberta/Calgary

- Alberta Health Services—Psychosocial Oncology: www.albertahealthservices.ca/cancer/Page17172.aspx. Provides professional support—psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, spiritual care providers—for patients and family members.

British Columbia/Vancouver

- BC Cancer—Family and Patient Counselling: www.bccancer.bc.ca/our-services/services/supportive-care/patient-family-counselling. Offers individual or group counselling sessions for people experiencing negative emotions, social tensions, or financial issues related to their cancer treatment.

Private practice

Check with your insurance company to see what kind of coverage you may have for private services if they are not covered by your provincial plan.

Quebec/Montreal

- Ordre des psychologues du Quebec: www.ordrepsy.qc.ca. Provides help finding a psychologist or psychotherapist in private practice.

- Montreal Therapy Centre: www.montrealtherapy.com. Offers individual, couples and family counseling. Sliding fee scale rates available.

- The Argyle Institute: www.argyleinstitute.org. Offers individual, couples and family counseling. Rates determined by household income.

Ontario/Toronto

- College of Psychologists of Ontario: cpo.on.ca. Provides information on psychologists in the province. You can filter by specialty.

- CBT Associates: www.cbtassociates.com/coping-with-cancer. Provides psychosocial support for mental health issues and concerns for those coping with cancer.

- Toronto Psychology Clinic: torontopsychology.com. Provides individual or couples counselling, with varying rates.

- Main St. Psychological Centre: www.mspc.ca/our-services. This clinic offers individual or family counselling, with rates varying according to the qualifications of each therapist.

Alberta/Calgary

- Psychologists’ Association of Alberta: psychologistsassociation.ab.ca. Can help you find a registered psychologist in your area.